- Home

- Damean Posner

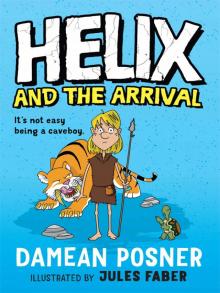

Helix and the Arrival Page 4

Helix and the Arrival Read online

Page 4

Speel sees me looking at the tablet and places his hand down over it. For a moment our three eyes lock and we are having our own private conversation.

Helix: Why can’t I look at it?

Speel: I don’t have to give you a reason.

Helix: That was a very long description of how terrible river people are, but I can only see a small number of word signs on the tablet …

Speel: I am the Storykeeper. Whatever I say is the truth.

Helix: That’s your answer for everything, isn’t it?

Speel: La, la, la … Not listening …

Speel clears his throat. ‘That will be all for today,’ he says. ‘You are both dismissed.’

We leave the stifling warmth of his cave and return to the sunshine and fresh air of the mountain. We’ve barely taken a step, though, before Saleeka ambushes us.

‘What did he say? What was your Learning about?’

‘Believe me,’ I say, ‘it was not that interesting. Nothing you probably don’t already know. Apparently, though, I found a sacred rock near Newstone. Fancy a trip there tomorrow?’

‘Newstone? I’m not going there. My father has been talking about Newstone, me, marriage and some guy named Nobak all in the same sentence.’

‘Isn’t he the guy who shaves his back hair?’ I ask.

‘That’s him. Mister Bald Back. Shaves it every third day with a flint blade, apparently.’

‘What a bonehead.’ I turn to Ug. ‘How about you?’

‘Me? I do not shave my back.’

‘I know you don’t shave your back – you’re hairier than a bison. I mean, do you want to come with me to Newstone tomorrow?’

‘Tomorrow? I cannot. My father wants me to hunt with him.’

‘Can you get out of it?’ I say.

‘No. He is going deep into the woods and might need help carrying his catch home. It could be huge.’ Ug’s eyes light up at the thought of capturing something massive.

Looks like it’s just me and my imaginary sacred rock.

Newstone is a mostly downhill walk along the Common Way. By leaving in the morning, I’ll arrive well before the middle part of the day.

It’s only in the past few years that mountain folk have begun to settle in Newstone. Those not in favour of Newstone, which is almost everyone in Rockfall, say it’s a dangerous place to live because you can’t keep an eye on the river people, like we can from Rockfall. But the caves are bigger – huge, in fact – and drier. There’s plenty of fresh water nearby and, because it’s a newer settlement, there are more beasts to hunt in the nearby woods.

Mum has wrapped some dried meat in a skin and tied it securely with a long strap leaf. She’s also given me a bladder full of water. Most mothers would be expecting their sons to take a detour off into the woods, spear a creature for lunch and bring back something extra for dinner, but my mum says, ‘Make sure you don’t wander off the Common Way!’ She knows that if I step foot into the woods, I’m more likely to become food than to find food.

Dad appears. ‘Yes, son. Stick to the path. The woods below are full of large beasts.’

‘None of which has been caught by you!’ says Mum to Dad.

‘That’s not true,’ says Dad. ‘Remember that poison-toothed tusk boar I brought back for my Arrival?’

‘That was half a tusk boar – the rest had been eaten by something bigger. And, anyway, Ugthorn told you where to find it.’

‘It was still in the woods,’ says Dad, defending himself.

‘The high woods, it was,’ says Mum. ‘And you sprinted in and sprinted out. Remember? Everyone in Rockfall saw you!’

‘Now that’s an exaggeration!’

If I wait for them to finish I won’t get back to Rockfall by dark. ‘See you later,’ I say, waving to them as I leave our cave.

The first part of my journey takes me between boulders that are almost big enough to be mountains. I feel hemmed in by the giant walls of stone on either side of me.

As the boulders become smaller and the path opens up, a clear view of the woods leading down to the river and the lowlands reveals itself. The river is sparkling blue. It curves one way and then the other, like an endless swollen serpent. Beyond it, I spot tiny moving figures. They are the river people going about their daily lives. Some are beside the river, though they are too far away for me to see exactly what they are doing. Others are closer to their homes – strange homes that are round and made of dried mud and tree branches.

Mountain folk, who all live in caves, think these roundhouses are ridiculous. Why would anyone choose to surround themselves with a mud wall and a roof of twigs? In the eyes of mountain folk, they are the homes of those who wished they lived in caves.

I think of everything I’ve been taught about the river people. All of my knowledge has come from the sacred tablets Speel keeps. The river people:

grew from the lowland mud, whereas mountain folk fell from the heavens

were not seen as worthy to dwell in caves, so were forced to build huts made from the putrid lowland mud

grow food from the sodden earth, because they are not skilled at hunting like the mountain folk

must never cross the river into the woods, as this land belongs to mountain folk.

There are lots of other writings on the river people. These are just some of the common ones that are told and retold.

I turn my attention away from the river people and continue to walk. Ahead, the Common Way bends back towards the mountain, hiding whatever lies ahead of me. There’ve been no other travellers on the path this morning, so as I approach the blind corner I don’t think to slow down. I’m walking with my head low and my mind quiet when all of a sudden I’m flattened by a mass of bristly muscle.

My back hits the ground hard and I find myself looking up at a pink snout and a pair of small fluttering eyes. I’m having trouble breathing – all of the beast’s weight is on my chest. I can see its teeth, its two big pointy teeth that jut out of its bottom jaw. A poison-toothed tusk boar! I’m about to be killed by a poison-toothed tusk boar! Its warm breath forms a blanket over my face and smells worse than Sherwin’s feet. Its mouth opens … The end is coming …

But instead of plunging its teeth into my throat, it licks my face from chin to forehead.

What?

‘Get off me!’ I yell.

‘Young Helix, is that you?’ says a smiling man with curly orange hair and a beard tied neatly into a bunch below his chin.

It’s Steckman. Slung over his shoulder is a large sack and hanging from different parts of his body are at least ten smaller ones, full of goods to trade. On the mountain, Steckman is known as a cave-to-cave salesman, trading his goods to anyone who wants them. He doesn’t belong to any one clan and is seen as an outsider by mountain folk, though they are happy enough to buy a sacred rock or panthera skin from him when they’re in the mood.

‘Yes, it’s me,’ I say, trying to find enough air to talk.

‘Porgo. Porgo! Porgo! Get off him!’ Steckman puts a rope vine around the creature’s belly and drags it off me. It takes all of Steckman’s weight and quite a bit of groaning, but eventually the beast moves away and sits down with its back against a rock.

‘Poison. Toothed. Tusk. Boar,’ I pant, scrabbling to my feet and pointing at the creature slumped against the rock.

Steckman laughs. ‘Have you ever seen a poison-toothed tusk boar? Five times the size of this girl and much more interested in eating you than licking you. No, Porgo is a swamp boar. I’m taming her so that she can be sold as a pet.’

‘A pet?’ I say. ‘Wha–’

‘Sorry, forgot who I was talking to. You mountain folk are behind the times, you know. Pets are becoming very popular in the lowlands.’

‘What are they for?’ I ask.

‘They’re … They’re animals that aren’t for eating.’

‘Do you mean like the lowland oxen kept by the river people?’ I ask.

‘Not exactly,’ says Steckman.

‘The oxen are working animals. Pets are for companionship.’

I look across at Porgo with her round pink torso, brown spots and bristly hide. Her breathing is made up of a combination of snorts and grunts, and I’m pretty sure I can still smell her putrid breath from here.

‘No offence, but who is going to buy Porgo?’

Steckman tenses up. ‘I’ll sell her. I just need to find the right buyer.’

‘You mean the river people?’ I say.

‘Maybe. They already have their lowland dogs for pets, but I’m hoping they will accept a swamp boar as well.’

‘Wouldn’t they want to eat her instead?’ I’m certain that if someone on the mountain spotted her, they would be thinking, ‘Dinner.’

‘Oh no,’ laughs Steckman. ‘Have you ever tasted swamp boar? Plargh!’

As if she can hear us, Porgo gets to her feet and starts snorting defiantly into the air.

‘See? She’s a character, isn’t she?’ says Steckman.

‘You’d better keep her away from mountain folk,’ I say.

‘That’s good advice, young Helix. Thank you.’

‘Have you just come from Newstone?’ I say.

‘Sure have. They’re my best customers on the mountain. Always wanting the latest goods I have to offer. Sold three pairs of mammoth-skin boots this morning. Would have sold twelve pairs had I not run out.’

‘Wow! Mammoth-skin boots! I bet they’d be warm in winter. So where are you off to now?’ I ask.

‘Aw, back to Rockfall,’ he says.

‘You don’t sound very excited about it.’

‘Would you be? I have to put up with that Speel giving me his sly one-eyed look and old Korg the Magnificent, who will make me attend to him in his cave and show him what I’ve got to offer. And always, always, it will end the same way, with Korg saying, “Nothing of any interest to me in that lot,” and I’ll have wasted half a day sipping bark tea with him. They’re a strange lot, your mob in Rockfall, Helix.’

‘Tell me about it,’ I say. ‘At least you don’t have to live there.’

Steckman begins gathering his sacks in preparation to go, but I have one last thing I need to ask. ‘Steckman, you know the river people –’

‘Sorry, Helix,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘I’ve been forbidden by Speel to talk of them.’

Porgo has her head on her side, as if she’s trying to understand what’s being said.

‘But why? You know more about the river people than he does.’

‘Perhaps so. Nevertheless, for now I’d prefer to keep my lips shut. If that meddling Speel finds out I’ve been talking about the river people, I’ll be banished from the mountain. Do you know what that would mean to my business?’

‘Steckman,’ I say, ‘it’s just you and me. I’ve seen no one else walk this path all morning.’ I peek around the corner to see if anyone is coming. ‘See? No one else is here. Please tell me – just a little about the river people.’

‘You’ve got to promise that if I tell you something – and I’m not saying that I will – you won’t mention a word to anyone back in Rockfall. Not a word.’

‘I absolutely promise,’ I say.

‘So what do you want to know?’ he says, stroking his orange beard.

‘Just … what they’re like,’ I say, unable to think of anything specific.

‘What they’re like,’ he repeats, pondering the question. ‘Not like your lot, that’s for sure.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They’re … different.’

‘I’ve heard they can’t hunt so need to grow their food from the mud,’ I say.

Steckman explodes in laughter. ‘Who told you that? Speel?’

‘Well, yes. Not that I really believe it … See, that’s the problem: I don’t know what to believe.’

‘How can I say this?’ he says, stroking his beard some more. ‘The river people are –’

I hear a noise. I turn and see a group of Rockfall cavemen, spears and heavy clubs in hand, approaching us on their way to a hunt. I turn back to Steckman, but he’s already gone. Porgo, however, is still sitting slumped against a rock. Two short whistles later, though, she springs to her feet and launches herself into the bushes in search of her master.

The cavemen have scared them off.

Great. So much for learning about the river people.

Newstone is, as you’d expect it to be, new. The caves look like they’ve only been lived in for one generation, and they have. Like their caves, the folk of Newstone also look fresh and clean – their eyes are bright and their hair is neat, not tangled and matted, which is the Rockfall style. No one walks with a hunch or a limp, and everyone looks well fed. They wear new loincloths that have been cut to the latest fashion – longer at the back and front and shorter at the sides. Everyone and everything looks so … new.

I pass Newstone’s store cave, which is much bigger and cleaner than Rockfall’s. I peer in and notice a range of different fresh and dried meats hanging from a timber beam. Compared to Rockfall’s store cave, where palm-square beasts are all that’s on offer, it’s pretty impressive.

Speel has an assistant Storykeeper in Newstone named Veldo. It’s from Veldo that I need to collect the writing skins for Speel.

Veldo’s cave is even bigger than Speel’s but then again, so are all the other caves in Newstone. All of them seem to be large, with high ceilings and deep passageways.

The bandi-twang at the entrance to Veldo’s cave has three strings. I strum the strings, thickest to thinnest, and they make a pleasant tune.

‘Yar, like, coming,’ says an airy voice from deep in the cave.

Folk from Newstone say ‘yar’ instead of ‘yes’, and they use the word ‘like’ a lot, not to mean anything, but just to fill the gaps between words. Rockfall folk find this way of talking very odd.

Veldo appears at the cave entrance, his arms hanging loosely by his side.

‘Hello, Veldo. My name is Helix. I’m from Rockfall.’

‘Yar, I can see that,’ he says, looking me up and down.

Veldo is a tall man. Tall and thin. His loincloth, as stylish as it is, is far too short for him and barely covers his man parts.

‘I’m here to collect some writing skins for Speel.’ Veldo points a long finger in the air and says, ‘Yar, of course. The writing skins. Come in and, like, make yourself at home.’

I enter his cave and am immediately impressed by how clean and big it is. On a rock shelf along one wall are displayed all sorts of interesting objects – rocks, bone carvings, mini-tablets and a row of animal teeth lined up from biggest to smallest. I take a few steps closer to get a better look.

‘I’m a collector,’ he says, as if he’s been bursting to make this confession.

‘I can see that,’ I say.

‘I try to collect objects from the woods and beyond – the, like, further away from the mountain, the more precious the object.’ He takes a big step towards the ledge and picks up a small, round, dark-blue rock with gold veins running through it. ‘See this? It’s, like, from the river.’

‘Have you been to the river?’ I ask, maybe a little too eagerly.

‘Oh no. No, no, no,’ he says, repeating his ‘no’ many times to make his point clear. ‘Folk from the mountain shouldn’t go to the river. And, like, anyway, I’m assistant Storykeeper to Speel. My place is here, recording the stories of our people.’

Some of the excitement seems to have drained from Veldo upon mentioning Speel’s name.

‘But do you ever wonder what the river people might be like?’ I say.

He’s silent in thought as he ponders my question. ‘Yar, I, like, think of it a lot. Sometimes I climb to a high place and look down at the river’s beauty. But … But then I see its size and the river people beyond.’ He stops another moment to ponder something. ‘There are many tablets, you know – many tablets that talk of the river people.’

‘What do they say?’ I ask.

‘Bad things, all bad things.’ He has a worried look on his face.

‘Yes, but what bad things?’ I really want to know.

Veldo looks up at the roof of the cave as if he’s searching for an answer to my question. ‘You know – like, they were born in the mud, they eat food from the ground, they have those pitiful mud houses … All that sort of thing.’

‘Have you seen any of this yourself?’ I say.

‘Seen? Like, of course not!’

‘But you believe what is written?’

‘Yar, it is written so it, like, must be true,’ he says, his hands forming fists at the end of his long-boned arms.

I change the subject. ‘I must admit, this is an impressive cave you’ve got, Veldo.’

‘Thanks. I’ve tried to give it a little of my own, like, personality.’

Instead of three separate fires as there are in Speel’s cave – one for cooking, one for stonehacks and one for Speel – there’s a single large fire in the middle of Veldo’s cave. On one side of the fire sits a stonehack, who’s working on translating word signs from skins to tablets.

‘How rude of me,’ says Veldo. ‘Helix, this is Mason. He, like, works for me doing the carving bits and bobs.’

‘Hi,’ says Mason, with a smile. ‘It’s, like, a real pleasure to meet you.’ He sticks out his giant calloused hand and shakes my tiny hand inside it.

‘Nice to meet you, too,’ I say.

Mason is big and strong, much like Crag and Tor. His forearms are like heavy clubs and his fists are like boulders. Unlike Crag and Tor, though, he seems a bit more relaxed – his brow isn’t as furrowed and his eyes are softer.

‘Isn’t it about time you, like, took a break?’ says Veldo to Mason.

‘I’ll just finish this tablet,’ says Mason.

Although I’ve visited Newstone before, I’ve never really spoken to anyone or had a proper look inside a cave. I feel as though I’ve arrived in another world. How can Veldo talk to his stonehack like this, as if they’re … as if they’re equal? I can’t imagine Speel ever asking Crag or Tor if they’d like a break.

Helix and the Arrival

Helix and the Arrival